Okay, so full transparency: this post isn’t about making boatloads of cash. Disappointing, I know. It’s an unfortunate truth that I’m not an elite member of that 1%, but if I ever do get there, I’ll be sure to draft up a guide with step-by-step instructions to join me. The 1% I’m talking about here are the wildly insane and obnoxiously loud individuals1 who actively choose to run a marathon.

That’s right, this post is about long distance running, a sport I hate and love every damn time I lace up my shoes.

If you’re already bored, I get it—that’s how I feel at the beginning of my training runs, and in the middle, and often by the end. If you choose not to stick around for this post, before you duck out, please consider donating to my fundraising campaign for the New York City Marathon I’ll be running on November 3rd. My running buddy (hi, Amanda!) and I are racing with Team Shoe4Africa, a charity that is raising money to build the first pediatric cancer hospital in sub-Saharan Africa!

And if you are sticking around, please also donate! Every dollar helps (and we’re 30% away from our goal)—we’re saving precious young lives here, folks! (Seriously, 9 in 10 children diagnosed with cancer in that region don’t survive—a nauseating statistic that emphasizes the importance of this endeavor).

Why I Run

I said it before and I’ll say it again: I don’t actually enjoy running while it’s happening. In fact, I consider this sport Type II fun (fun in retrospect, somehow). And that’s not to say that I haven’t been on runs with perfect temperatures on beautiful days that actually feel amazing the entire time—I’ve had a few of those blissful experiences, but they’re few and far between. Running, for me, is pretty torturous and whenever I explain that to non-runners, they immediately ask why I do it. Why the hell would I commit so much time and energy to something I don’t even enjoy? Why do I love something I also genuinely hate?

Believe me, I ask myself these questions every Saturday morning when my alarm goes off before the sun rises and I have to force myself to eat something at an hour when my body is in full revolt mode. And it’s not like I’m racing to win—there’s no way in hell I’ll ever come close to winning any sort of race.2

The honest truth is that I sign up for these races for two primary reasons:

I have an insatiable desire for some kind of control in my life, and so much of my life’s experiences are outside of my control, so it’s nice to have an activity that enables me to feel in control of something.

I want to enjoy running, and I want to be good at it (and by good I mean fast and uninjured), and I don’t and I’m not, so I’ll probably keep doing this until I do and I am. See my hot take on the running bug below.

A Series of Anecdotes Many Runners Can Relate To

Two years ago, Amanda decided that she was going to run her first marathon. I had a conference on the other side of the country that weekend so I couldn’t do the race with her, but I did try to join her for most of her long runs on the weekends.

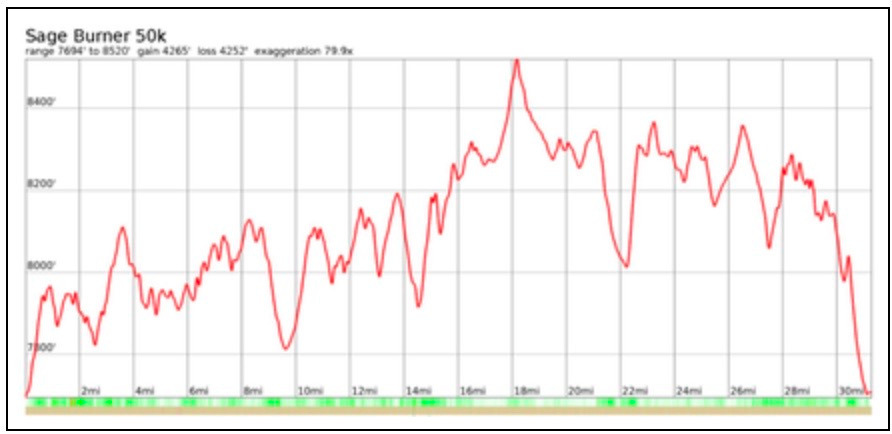

Anecdote 1: It had been almost four years since my last race, a 50K ultra marathon called The Sage Burner. It’s a race Dave and I have done more than once, and one I would be absolutely willing to do again if it were still hosted by Mad Moose. However, it is not, and I think I’ve made it past the phase where it seems exciting to drag my ass 31 miles through mountainous terrain.

The race starts with a steep incline (elevation profile below) at 7 am, at an elevation so high that temperatures in the teens are considered excellent conditions. That year (2018), it was 12 degrees at the start, 16 degrees two hours later, and I made the stupid mistake of failing to blow the water back into my Camelback bladder less than a mile into the race so the tube froze and I had to run with both (frozen) hands wrapped around the straw in a desperate attempt to melt the ice and avoid, I donno, dying of dehydration out in the wilderness?!

I mention the temperature because if you’ve ever been in those conditions, you probably have a decent understanding of the numbness that takes hold of your whole body. Add in the fact that I was sweating and that sweat freezes pretty readily in those temperatures, and you’ve got a fun little recipe for hypothermia and the only way to avoid succumbing is to keep moving. But the point is that, by mile 7, my foot was hurting, and even my brain was too numb and paralyzed to consider that I might be injured—it’s impossible for me to distinguish between injury (the only con to having a ridiculously high pain tolerance) and mere discomfort, particularly when you’re essentially a human popsicle engaging in an arguably inhuman feat of physical exertion.

So I stupidly “ran3” the remaining 24 miles, over thousands of feet of elevation gain, on a foot that was hurting (but also numb?) for the vast majority of the 7+ hours I was out there. As it turns out, that foot was pretty fractured in a few places, and I wound up in one of those fun space boots for almost four months while it healed.4

Anecdote 2: I hadn’t run since that injury and instead spent most of my time focusing on strength training and Peloton cycling, but I figured I had taken a long enough break from running that I could will myself to join my friend on her journey to 26.2. At around the halfway point in her training, Amanda said to me on one of our runs that she would never, ever, ever in a million years choose do this again. And I laughed and turned to her and said “Sure, but wait until three days after the race, when the amnesia hits—you’ll be texting me asking which race we should sign up for next.”

And so it goes: Amanda runs her race in North Carolina (the same day as the New York City marathon that year), in some of the most miserable conditions (alone, and on one of the hottest days on record). Three days later, I got a text saying, “Want to put in for the Chicago Marathon lottery?” Like fucking clockwork, Amanda had caught the running bug.

I agreed to submit my name, because we thought there was no way we would both make it into the race. However, we’re a pretty lucky duo and were both offered a bib. We told ourselves that we would continue running after Amanda had taken a few weeks to recover after her race, so that we would have a strong foundation heading into the new training cycle (which, for us, started in May).

We most definitely did not. I can’t speak for Amanda, but I ran a grand total of four times between the Chicago Marathon and the start of our current training schedule for New York. The first was a Turkey Trot 5K in Florida, the day after breaking one of my toes jumping into a pool, and the other three runs happened two weeks before training started. This happens every time, without fail. Now is as good of time as any to admit that, if I do in fact sign up for another one of these things, I’ll continue to make the choice—my brain and body houses zero intrinsic motivation to run.

Anyway: I agreed to run Chicago, my first road marathon, and my first one of the World Majors. And I wasn’t expecting it to be so fun (until mile 23, when you reach a juncture wherein you can see thousands of runners heading left toward the finish while you have to head to the right for a mile and a half before turning around to head toward the finish—a cruel mindfuck for the tired, sore, and weary).

Amanda and I crossed the start line a few minutes before Kiptum set the marathon world record on the same course that day, and despite being the last group of runners to take off, tens of thousands of people lined the streets for all 26.2 miles, screaming and cheering, holding signs5, and offering shots.

I don’t remember if it was the requisite three-days-later or maybe a few additional days, but I do remember that it wasn’t long before I started trying to convince Amanda that we had to run NYC before retiring from the sport.

And so, we’ll be hitting the pavement in all five boroughs on November 3rd, 2024 with our typical three goals in mind:

Finish the race.

Don’t finish last.

Finish under 5:45.

The Running Bug: A Bona Fide Illness

There’s something genuinely sick about long-distance runners.

At a certain point in the training process, we say crazy, outlandish things like: “I only have to run 10 miles tomorrow” and “Can we plan for a 5:30 dinner because I have to set a 4:30 am alarm to run 18 miles before it gets too hot?”.

We have intimate discussions about our bodies before, during, and after each run. Before long runs, I’ve learned to consume the perfect amount of sustenance to avoid significant nausea without hurting my stomach. I’ve also learned the perfect timing for coffee consumption and taking coffee’s fun antidote6. Amanda has supported me when I’ve had to stop running because my knee hurts, or I can’t breathe, or I have a migraine, or I’m overheated, or my pancreas is failing, or I think (I know) I have a UTI (a fun discovery/realization mid-run). I’ll spare you the details of the frequency in which I wind up vomiting before, during, or after a run. And for what it’s worth, I’ve supported her through many of the somehow more pleasant of these things, too.

But the real illness is the fact that we finish these marathons (the plurality here is pretty sick in and of itself), a whole 26.2 miles, and that’s not even the hard part.

The hard part is the discipline required to sacrifice a good chunk of every weekend, for four months (Friday night early to bed, Saturday morning early to rise, not fully functional for the rest of the day after the long run, and feeling too mentally and physically exhausted to chase away the Sunday Scaries). The hard part is committing to running on vacation, no matter the temperature or other planned activities. The hard part is starting many long runs with a headlight because if you wait until the sun is up, the heat will mercilessly beat you down, a direct and disastrous blow to the body and psyche alike. The hard part is being invariably slow, which means we are out there on our feet longer than most, and our hearts and lungs are operating in overdrive for extended periods of time. The hard part is remembering to hydrate well before, during, and after each run. The hard part is running 400+ miles in preparation for race day, breaking in and destroying at least two pairs of shoes in the process, spending well over 100 hours putting one foot in front of the other, desperately searching for any semblance of distraction from the pain, discomfort, frustration, and lack of oxygen.

But the hardest part, the greatest indicator that The Illness has taken over, is getting through the first weekend after the race, when the alarm doesn’t go off before the sun, you don’t lace up your shoes or fill the bladder to shove into your running vest, and you suddenly have too much time on your hands.

The Aftermath

When the race is over, I tend to feel rudderless, lacking forward momentum, both literally and figuratively. I have yet to discover another passion or hobby or activity that requires the same level of structure and discipline and determination and fortitude and tenacity.

I keep saying that this New York City Marathon will be my last race, but I’ve said that before, and if I’m being honest with myself, I’ll probably wind up saying it again. This one has been a bucket list item since I started running in 2011, inspired by my husband who is one of those infuriating people who can go months without running and then lace up his shoes and knock out 8 miles faster than me at my fastest. I just want to be faster than him, and so I keep doing these things.

The vibe and energy of The Chicago Marathon is going to be hard to top, but

(a guy who knows more about NYC vibes than anyone else I know) claims “[the NYC Marathon] is, bar none, the happiest day of the year in New York, always”. I want to experience that.The truth is, I do indeed run for the two reasons listed above. But I also sign up for these things to give my life purpose, to have my sights set on a goal with tangible (literal) steps to get there, to ensure that I carve out me time7 in my busy and hectic life.

I already can’t wait to be done with the 15 miles we have to run tomorrow morning.

You know who they (we) are, because they (we) can’t stop talking about it.

There’s probably a really great joke here about winning the human race, but I can’t quite put a finger on how to articulate it, so just know that it’s rolling around in the contours of my overactive brain.

More like speed-hiked with relative enthusiasm

When Dave ran the same race a year or two later, he DNF’d (Did Not Finish) just to prove a point to me that it’s okay to stop mid-race.

My favorite read: You think this is hard? Try dating in Chicago!

And some deeply misinformed young woman held a sign that said “All this for a free t-shirt?” and I kept yelling at her every time I saw her that we actually had to pay close to $400 for that t-shirt.

Immodium.

Because, while we are raising money for charity and there are runners out there who are running “for” someone or something, the reality is that we do this for ourselves, for our physical and mental health, to test the limits of our human capabilities.